Henrikas (Henry) Salkauskas (1925-1979), artist and house-painter, was born on 6 May 1925 at Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania, the only child of Henrikas Salkauskas, army officer, and his wife Ona-Anna, née Sidzikauskas.

Henry Šalkauskas

Broad collisions of shape and colour create a wondrous change for Australian art

“Behind is always the Sun”

His father and other patriots were taken away by the Russians in 1940 and never seen by the family again. At the age of 15, Henry saw his father answer the knock on the door of their home and witnessed his father’s face whiten as a policeman, a soldier and a gestapo officer came to take him away. His father turned to him and begged him to “look after your mother” as he was led away. It was not until 1958 that young Henrikas was informed that his father had died in the Vorkuta concentration camp, Siberia.

He and his mother fled ahead of the advancing Russian army in 1944. They settled at Freiburg, West Germany. Henrikas studied at the university and at L’Ecole des Arts et Métiers, specializing in the graphic arts; Ona-Anna graduated in medicine. On 31 May 1949 they reached Melbourne in the Skaugum with his artist friends, Pranas Repsys and Viktoras Simankevicius. Henry, as he was known in Australia, worked under contract in a stone-quarry in Canberra for two years. He began to exhibit his linocut prints.

Early Life

Moving to Sydney in 1951, Salkauskas lived at Kirribilli from 1954. In the mid-1950s he painted stations for the New South Wales Government Railways and Tramways. He worked as a house-painter for the rest of his life. In 1958 he was naturalized. A friend of many artists, he was a committee-member (from 1957) of the Sydney branch of the Contemporary Art Society of Australia and a founder (1961) of the Sydney Printmakers. He eagerly promoted printmaking and helped to organize exhibitions of graphic art, nationally and internationally. In 1960 he met the Lithuanian-born artist, Eva Kubbos. They worked together and showed in group exhibitions and competitions. Of his one-man exhibition at the Macquarie Galleries in June 1961, the Sydney Morning Herald critic commented: ‘Salkauskas proves himself one of Sydney’s best graphic artists’.

Salkauskas represented Australia in major international print exhibitions at São Paulo, Brazil (1960), Tokyo (1960 and 1962), South East Asia (1962) and Ljubljana, Yugoslavia (1963). Yet in 1965 he turned his attention to painting large watercolours in the abstract-impressionist style. He thought that most water-colourists were too cautious. His method was to place a large sheet of Stonehenge paper on the floor; then, using big brushes, sponges and rags, he manipulated the flow of the dense washes of blacks and greys across the paper until his eye was satisfied with the result. In 1963 he joined the Australian Watercolour Institute and proceeded to revitalize the medium.

The reasons why Salkauskas used blacks and greys extensively in his paintings were complex. They involved his anguish at what had happened to his father, the influence of the Lithuanian winter landscape with its sharp contrasts of black silhouettes against snow, and the Lithuanian graphic tradition of printing in black and white. Despite this restricted palette, his tonal paintings were full of vitality and often involved an expressive use of symbols.

Of the few photos left of Salkauskas, this one by David Moore best captures the artist in action.

Major Australian art prize winner

In Australia, Salkauskas won over sixty art awards, among them the Perth prize (1963), the grand prize for the Mirror-Waratah Festival (1963), Sydney, and the Maude Vizard-Wholohan prize (Adelaide).

The ‘big, blond, amiable Lithuanian’ never married. He died suddenly of myocardial ischaemia on 31 August 1979 at his Kirribilli home and was cremated.

His work is represented in national, State and regional galleries in Australia.

The Art Gallery of New South Wales held a retrospective exhibition in 1981 and established the Henry Salkauskas Contemporary Art purchase award.

His first ever retrospective back in his motherland was held at the Vytauto Kasiulio Muzejus in late 2018. A wonderful collection of his artwork was donated to the museum by his fellow painter and colleague, Eva Kubbos.

James Gleeson interviews Henry Salkauskas

Elwyn Lynn on Šalkauskas (1966):

Besides many individual and group shows in Australia, Šalkauskas has exhibited widely internationally. He has participated in the following group shows outside Australia: Riverside Museum, New York (1958) Lithuanian Prints and Drawings, Auckland New Zeland (1959); Second International Biennale of Prints, Tokyo (1960); Fifteen Australians, London and Newcastle-on-Tyne (1960); Sao Paulo Biennale (1961); Third International Biennale of Prints, Tokyo (1962); Four Arts in Australia, Traveling Exhibition, South-East Asia (1962); Prints of the World, London (1962); Fifth International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia (1963); International Exhibition of Prints and Drawings, Lugano, Switzerland (196i); Young Australian Printers, Tokyo and Kyoto (1965); Australian Print-makers, Washington, D.C. (1966).

In Australia Šalkauskas has won over twenty-five prizes for water-colours and prints — a number that indicates only a few of the shows in which he has participated — and this has meant that his work has been widely seen and commented upon. Such recognition has allowed him to arouse interest not only in his aesthetic but also in his craft of print-making and in a water-colour technique that involves vast pale washes and stains and sudden dramatic areas of funereal black.

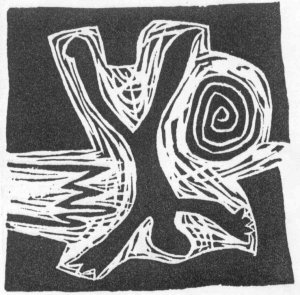

Šalkauskas, like most abstract or abstracting painters, was affected by the belated wave of abstract expressionism that swept Sydney in late 1956; but at that time he was still concerned to preserve discipline — mainly through the use of lino-cuts, but, as can be seen in Behind is Always the Sun (1962), he was always concerned to retain certain areas as reservoirs of energy as entities and presences in themselves rather than have them lost in action painting’s vortex. In this work his horizontal palisade presages much of his later use of free-floating islands of blackness. Of course, the skill, variation of form, inventiveness and imaginative use of emphasis that characterize all his work is evident here.

Šalkauskas was absorbing the modes and purposes of action painting when notions of hard-edge, colour-field and colour-imagery began to influence artists in Australia, and what was distinctive and significant about his work is the way his calligraphy, his home-spun ideograms have been elevated to images, to almost hard-edge shapes, and the abstract expressionist elements of loose washes and accidents have been relegated to the background. Rauschenberg, for example, in his assemblages, used the action-painting brush stroke as one collage ingredient, but Šalkaukas, in giving action-painting techniques and the emotional content they imply a subsidiary role, still makes them a formidable part of his compositions. In Drawing for a Great Aviator (1966) where the cross conjures up notions of propellers and iron crosses, the circle could be interpreted as a plane itself; but the black band across the top rejects such associative and interpretative excursions and emphasizes the tension between the modes. That he is concerned with the symbolic opposition of forms, with the dramatic arresting of the movements of giant areas that have become masses in motion is evident in a watercolour like Edge of Spring (1965). In the latter it is clear what he took from action painting; the act of creation and the created object are one; the solid black inseminates, as it were, the invading, almost amorphous form on the left.

As with many contemporary artists the process is as important as the finished work. He shares with the early cubists — who, too, wanted to demonstrate their methods of analysis, to show how it was done — a concern with the capture and release of forms, here exemplified in Painting 10 (1966) where the imprisoned stains coalesce into tough orbs, rejecting their amorphous origins. A similar process occurs in the water-colour Around the Window (1966) where the great black walls that enclose the abyss may be in danger of dissolution from the whispy shapes floating within.

Šalkauskas has long been preoccupied with the opposition between solidity and liquescence and in Rainy Zone (196A) and in Drawing (1965), which won the prestigious Perth Prize, the processes of fluidity, of melting forms or, contrarily, the crystalization of black forms from transitory washes, dominate his thought and methods. He often uses a band of black to still, arrest and fix the process; this is probably why STOP became the slogan of Stop Painting (1965-6) when it seemed that the stabilizing black horizontal band at the bottom was not enough. Such puns indicate the ambiguity of his purposes, a concern with being and becoming that occurs even in such calculated processes as his serigraphs where forms curve or jut (Serigraph and Serigraph 2) with a tremulous vigour, a tense balance and a vitality not usually associated with this method. In fact, his use of serigraph reveals how much Šalkauskas is opposed to decorative deployment of forms, to fastidious placement, for he remains a proponent of the expressive shape, of the immediacy of the monumental form, and he, and his fellow Lithuanians have given to Australia’s rather brash expressionism an intensified elegance that does not conceal the underlying vigour.

< Elwyn Lynn was President of the Contemporary Art Society (N.S.W. Branch), an art critic for the national newspaper The Australian, and an artist himself.>

His re-design of the masthead for the Australian Lithuanian newspaper “Musu Pastoge” in the 1960’s remains to this day